Tourology: Photographs from the Bus

Salo Balik, Curator of Ethnographic, Photographic, Totemic and Fetishistic Collections, Ukbar University, Armenia

We’re surrounded by so many images that we must learn to weed out those we care least about. Of the ones we value, we cherry-pick—as Americans say—to suit our argument. Hoarding under the guise of a “theme” is the curator’s métier. Once curated, we must then teach—perhaps “post‑online” is the new teach—how to read that theme: opaquely, obliquely, transparently, tangentially. The teaching reverses the curation. Curation moves from lots of stuff to an ordered theme; presentation moves from that theme back to lots of stuff. We begin by reading across the surface of the artifacts: at first they “mean” nothing, then they “mean” everything. Like Schrödinger’s cat, they simultaneously mean-and-don’t-mean—latent, hidden, both dead and alive. Between the banks of the River of Nothing and Everything, our tedious theme careens.

“Tourology” is a grammar, a Logos — a framework of experience. The tourist is the observer of surfaces par excellence. Dots are never connected; things are known as discrete, atomic experiences, and then it stops. The vehicle that ferries the tourist across the River of Nothing–Everything is the tour bus. One cannot be “a” Tourist, as that implies unique touristic persons. There are none. One can only be “the” tourist: a Platonic copy machine faxing Borg‑like identical brands into the soft clay minds of travelers. The tourist is one observer, a catholic domain of homogeneous perception, a colossal network of geographies and industries. We have all suffered through a slide show of holiday snaps. This book is that slide show. The experience nascent to touring and holiday slides is ennui.

If this sounds lugubrious, let us cut with the other side of the sword: sweet surrender, inner gaiety, the passive pleasure of follow‑the‑leader. No critical thinking is wanted or required—critical thinking has been proven useless. Just look at the American president (2025). Critical thinking is tiresome, a cliché, a forgotten word in a world of fundamentalists. And thank God—maybe we can finally relax. This is my confession: I love being a tourist. True, an armchair tourist due to my obesity, but still. It is the experience of giving up—surrendering the sovereign mind and being conveyed to the next dot by the bus. What was just seen is now forgotten; what is to come can wait. Getting off the bus to see a site is the mirror image of pausing a TV show to get off the sofa to relieve yourself. What a relief! Now, in book form and without an electronic viewing device, I need not leave my village: the photographer has simulated a direct experience of a real place, albeit with artifice that this book lacks.

Consider the countless pictures of plates of food on Facebook and you see the dearth of meaningful emotional content that once promised transformation. The one who posted the image doesn’t care for the plate of food—and often doesn’t even know it. They believe the image “captures” the emotion, commingled with the memory of family celebrations or business triumphs. Three weeks later they look at the photo and wonder why they posted it: the feeling is gone, not even a trace recovered from the image. If filmmakers struggle to convey emotion through moving pictures, what right have you to inflict on your Facebook friends the failure of the still image? Spare us: delete your account.

Which brings me to this book. What do I see here? Dare I write it? Will the editor redact? This book bores me to death, then to tears. It slays me—not laughably. Yet this boredom may be the fundamental nature of what Tourology attempts to disclose—and from which it plots an escape. You needn’t go anywhere. Just “read” the pictures. Pour a whiskey to loosen stubborn tears. Surf Facebook for marginally more compelling images of food, dogs, deceased parents, graduations, neonates, or lamentable marriages. Photography is dead. Get over it. It cannot disclose or transfigure; at best it records that something might once have been there, like data without resonance, value, or care. Kaput. It is like looking through a filthy window: the stains and grime are palimpsestic floaters in the mind’s eye that occlude. Today the floaters are too large to look around. They require an ancient kind of surgery—perhaps a new kind of spiritual trepanning. A shame, really. Please, my friend, spare us: don’t publish. It’s been done already, and better, in the movies, which are already coughing up blood on the way out.

Lucian Edgar, Department of Philology and Archives, University of Jakarta

Whenever I look at a photograph, I cannot help but see only the two-dimensional window, precise, flat, and perfectly transparent: a tour-de-force of Fundamentalism, the defining quality of our contemporary consciousness. Scientific Materialism has stripped us of hermetic, mythical, poetic, archetypal readings that once possessed the power to transform our experience by mere Understanding. Instead, experiences are simply neurologically stacked, piled, like junk in a storage unit in a abandoned industrial “park” whose strata require the vision of a new kind of archeologist—if only we could care to look at it again, like the images on Facebook: that was then, only a forgotten record, an archive of personal subjective “culture” that can say only one thing, and badly: I was there. But who cares? The only response is to throw the entire lot overboard, and don’t look back. Since looking back turns one to stone. The window as metaphor, while trite, reduces the complex to the simple, on whose cleared parcel of figurative land a new edifice may be constructed, complexity may then be understood if only enough to be seen for what it was: jetsam.

A photograph is a near‑perfect transparent window: you don’t look at the photograph so much as through it, at something “real,” “there,” or “once there but no longer.” At the other end of the window metaphor sits the abstract painting: you don’t look through it but at its surface. Photography is therefore conservative and literal—recording what was once present and is now gone. Our response becomes, “See? The world has passed us by. It was better then.”

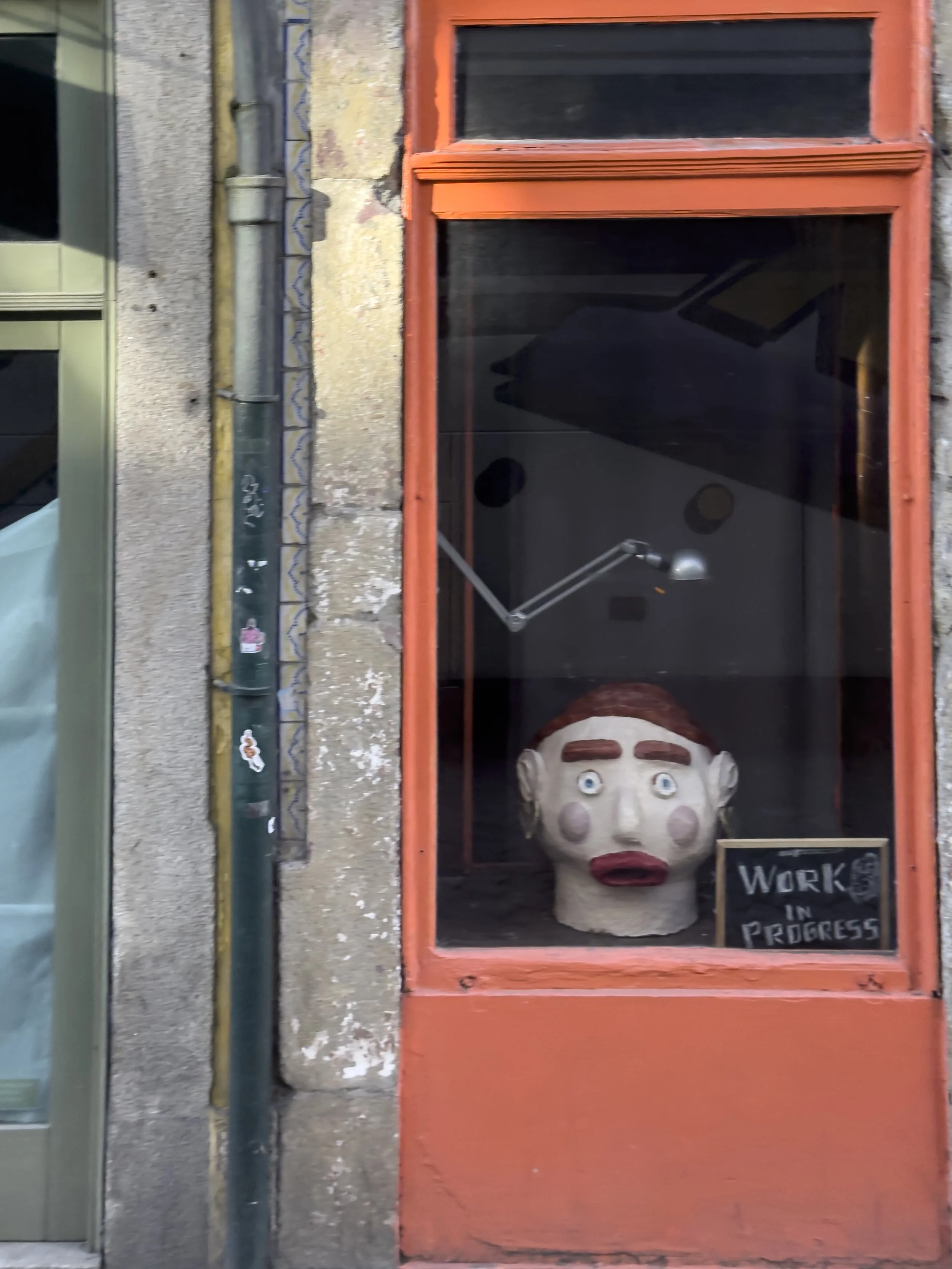

Between photograph and abstract painting lies the middle ground of realist painting, where brushwork is visible yet the subject remains recognizable. Here we perceive something rarely obvious in a photograph: the maker’s hand—brushstrokes that declare, “a human, like me, made this.” Is there anything special about this humanistic, conservative practice for the viewer? Not necessarily. For the maker, however, it’s a claim: “it’s all been done before—but not by me.”

Photographs can be sequenced to tell a story; then we return to the domain of possible transfiguration through understanding—if we take the time. Increasingly, we do not. The maker is no longer even wholly human: it is AI, the ersatz human and ersatz novelty—the final nail in the humanistic coffin. Would I be giving away the punch line if I declared that AI made the images in this book? Can we even know? Are there six fingers, deformed ears? Is a biological finger pressing the shutter enough?

When the walls of the sovereign mind are breached, the mind becomes a vassal of its enemy—an instrument. Photography is memory, now fake memory. Forgetting and erasing become joy. Do not photograph, for there is nothing worth remembering. Only then does the future open luminously possible—a sign of imminent joy amid the mind’s decay.Photography is memory, now fake-memory. Forgetting-erasing is Joy. Do not photograph as there is nothing worth remembering. Only then does the future stand lucidly possible, a sign of imminent Joy amidst the mental caries.

* * *

I wish to thank Salo Balik and Lucian Edgar.

Salo’s masterful command of critical cultural theory, elastic editorialship, and years of cohortship have contributed to this book in unorthodox and often hidden ways.

I met Salo in Istanbul in 1982, in one of those cafés where intellectuals ingest prodigious quantities of stimulants at all hours and utter clever-sounding gibberish. The café sat in a warren of narrow, labyrinthine alleys, surrounded by yellowing 1950s ads for cigarettes, coffee, and vodka in red, Eastern‑bloc typography that always struck me as unnecessarily menacing. The architecture was a grotesque blend of failed attempts at Greek symmetry and sarsen-like columns of Soviet sensibility. Nothing went together, and yet it added up to a kind of Eurasian glamour, like Russian housewives putting on makeup—childlike and earnest.

Salo was beautiful and rotund—no less than two hundred fifty pounds—with green eyes and dyed black, very short pageboy hair. She brought to mind a giant marks‑a‑lot. When she laughed we braced; her quaking corpus spilled drinks and sent plates crashing. She spoke twelve languages. British English broke from her mouth with the freedom of an escaped criminal, colored by the Armenian, lachrymose cadences of the duduk. From the next table she noticed the book I was reading—an English translation from French about mimetic contagion in ethnographic authorship—and, without invitation, claimed to know the author personally and to have slept with him. I was intrigued. She told me he liked to be pegged with a Yankees baseball bat he’d acquired at an academic conference in New York in the early 1970s. He loved American baseball because it possessed “levels of meaning.” I doubted the veracity of these claims from a stranger, yet I was jettisoned into her orbit like a rag doll—propelled by her confidence, the color of her accent, her monumental presence, the brilliance of her intellect, my low self‑esteem, and above all her laughter, which declared that a worldwide tragicomedy was unfolding before our eyes. The unspoken message: it is OK to be alive; we could relax in the arms of the dragon.

Lucian Edgar was a different story. Unlikeable, sullen, and creepy beyond words, he carried a presence that felt like a nerdy conspiracy to dismember any creative or scholarly effort—like a brooding prodigal American teenager who fantasized about “active shooters.” He dressed as if shrink‑wrapped for shipping and described himself as a “bête noire crossed with an enfant terrible.” In truth he was neither; he could be putty in the right hands. Why bother with someone so difficult? Because beneath his affected malice he exuded an innocence you could see through—like a freshly cleaned window straight into his heart. That was my first impression: lovable despite his efforts to make you hate him. We met in Argentina, where I was working on a petting farm as a fake gaucho for tourists after answering an ad on Gopher > International > Argentina > Tourism > Wanted > Gauchos/Clowns. Lucian Edgar died of a massive stroke during routine surgery to correct a hiatal hernia. I will miss him dearly.

—John Guillory